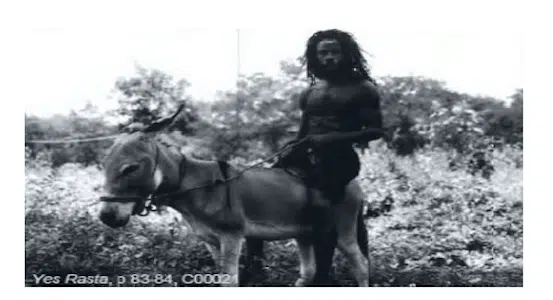

“Yes Rasta” was published in 2000; Cariou memorialized the several years he spent living with Rastas in Jamaica. Reportedly, Prince came across a copy of the book while browsing a St. Barth’s bookstore. He scavenged the photos and created a series of paintings and collages he called “Canal Zone,” which were sold in 2008 at the Gagosian Gallery in NYC.

Generally speaking, the fair use doctrine allows limited use of copyrighted material without the permission of the pre-existing copyright owner. The common law fair use exception was incorporated as part of the 1976 Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. § 107 :

“ Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 17 U.S.C. § 106 and 17 U.S.C. § 106A , the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting,teaching(includingmultiplecopiesforclassroomuse),scholarship,orresearch, isnot an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include:

the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

the nature of the copyrighted work;

the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a

whole; and

the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.”

Conceptually, the fair use doctrine is intended to stimulate creativity, enrich the public, advance knowledge, and progress the arts by adding something of new of value to a pre-existing work. If the new work merely copies or “supersedes” the original work purely for profit, the fair use exception will not apply.

In the Cariou c ase, the Federal District Judge ruled in Cariou’s favor and found that Prince’s use of the photos was not transformative, reasoning that the Prince artwork did not comment on the photos themselves and did not critically refer to them. As such, according the District Judge, this manifestation of Prince’s appropriation art did not qualify as fair use.

However, the Circuit Court of Appeals disagreed with the District Judge and reversed the ruling, finding the vast majority of the Prince works, which cannibalized Cariou’s photos to great commercial success, did not constitute copyright infringement, and did qualify under the fair use exception. The Circuit Court sent back just five photos for the District Court to reconsider under a different analysis, which does not require any per se reference to the primary works in the secondary works.

In rejecting the District Court’s analysis, the Circuit Court held that the language “ for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research ,” in the fair use statute was not intended to be an exhaustive list of valid purposes, but was merely illustrative. The Circuit Court held that it did not matter that Prince did not intend any particular “message” and did not intend to comment in any way on the original photos. In the final analysis, the Circuit Court found that Prince transformed C ariou’s photographs into something new and different, and that Prince’s audience was also different from that of the people who purchased Cariou’s book of photographs.

The Circuit Court then remanded, leaving open the possibility that five of Prince’s works (with alarmingly minimal alteration or “transformation”) may not qualify for the fair use exception, sending those five works back to Judge Batts to determine if, under the Circuit Court’s analysis, the works would qualify as fair use.

Aligned photographers are taking the position that the Circuit Court’s decision went too far in its application of the fair use doctrine, essentially putting a “steal this photo” label on photographs. Therefore, the case, on remand, provides a limited opportunity for (non)appropriation artists and photographers to challenge the application of the fair use doctrine at least with regard to five remaining Cariou photographs.

See

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/22/arts/design/photographers-band-together-to-protect-work-i n-fair-use-cases.html

Appropriation art is widely recognized in the arts community as a popular genre, which continues to thrive and grow beyond that which made Andy Warhol famous. The fair use doctrine will maintain its vitality and will be applied beyond the arts. Beyond, its central importance in education (Fair Use Guidelines for Educational Multimedia), which permits academics sufficient leeway in order to critically consider various works of intellectual property, the doctrine is important for innovation and creative development in all fields. Premised on the very core values of free speech, fair use can be viewed as not just an “exception” to copyright infringement, but as a rule governing expression.

However, the application of the doctrine can also give rise to economic inequities, particularly in the arts, inviting appropriation artists to essentially take, without remuneration or credit, another artist’s work and make it his or her own. If the secondary user is going to essentially completely take or borrow the primary work, as in the Prince-Cariou situation, there should at least be a

mandated acknowledgment or credit along with some equitable compensation of and for the primary creator’s copyright of the original work.

Photographers and other artists (particularly those involved with digital creations) should familiarize themselves with the standards applied. All works should be registered and the copyright notice should be applied on or adjacent to the photo or other work. For online media, technology should be used to prevent unauthorized downloading of your images. When a photographer or artist creates a work, thought should be given to creating multifarious manifestations of those works in order to secure the greatest range of protection as possible. Thought should be given to expanding commercial markets as broadly as feasible for a given photo or work. Making an effort to expand your markets may serve you well in the future in the event someone decides to make “fair” use of your work. There is a striking difference between the 2 Live Crew parody of the Roy Orbison “Pretty Woman” song and Prince’s unapologetic use of “Yes Rasta.” It is fair to say that the fair use doctrine has become the rule, rather than the exception.

Text or Call Giordano Law at: (646) 217-0749.

Related Posts

- Copyright infringement, David Beats Goliath (again)

In AFP v. Morel, 10 Civ. 02730 (AJN) ( SDNY Jan. 14, 2013) , Judge…

- Police Officer Tests

How are they selecting police officers these days? If you are ever selected as a…

- SDNY 1983 Plan

The federal court for the Southern District of New York (Manhattan, Bronx, Westchester, Putnam, Rockland,…